is an independent institution that facilitates collaborative

governance reforms to realize a more prosperous

Indonesia, by involving various parties

(government, political actors, civil society, and the private sector).

In the process, to ensure that development does not

harm one party (no one left behind),

KEMITRAAN in all its work mainstreams

the principles of inclusiveness, anti-corruption, human rights (HAM),

and gender equality.

is an independent institution that facilitates collaborative

governance reforms to realize a more prosperous

Indonesia, by involving various parties

(government, political actors, civil society, and the private sector).

In the process, to ensure that development does not

harm one party (no one left behind),

KEMITRAAN in all its work mainstreams

the principles of inclusiveness, anti-corruption, human rights (HAM),

and gender equality.

Latest

News

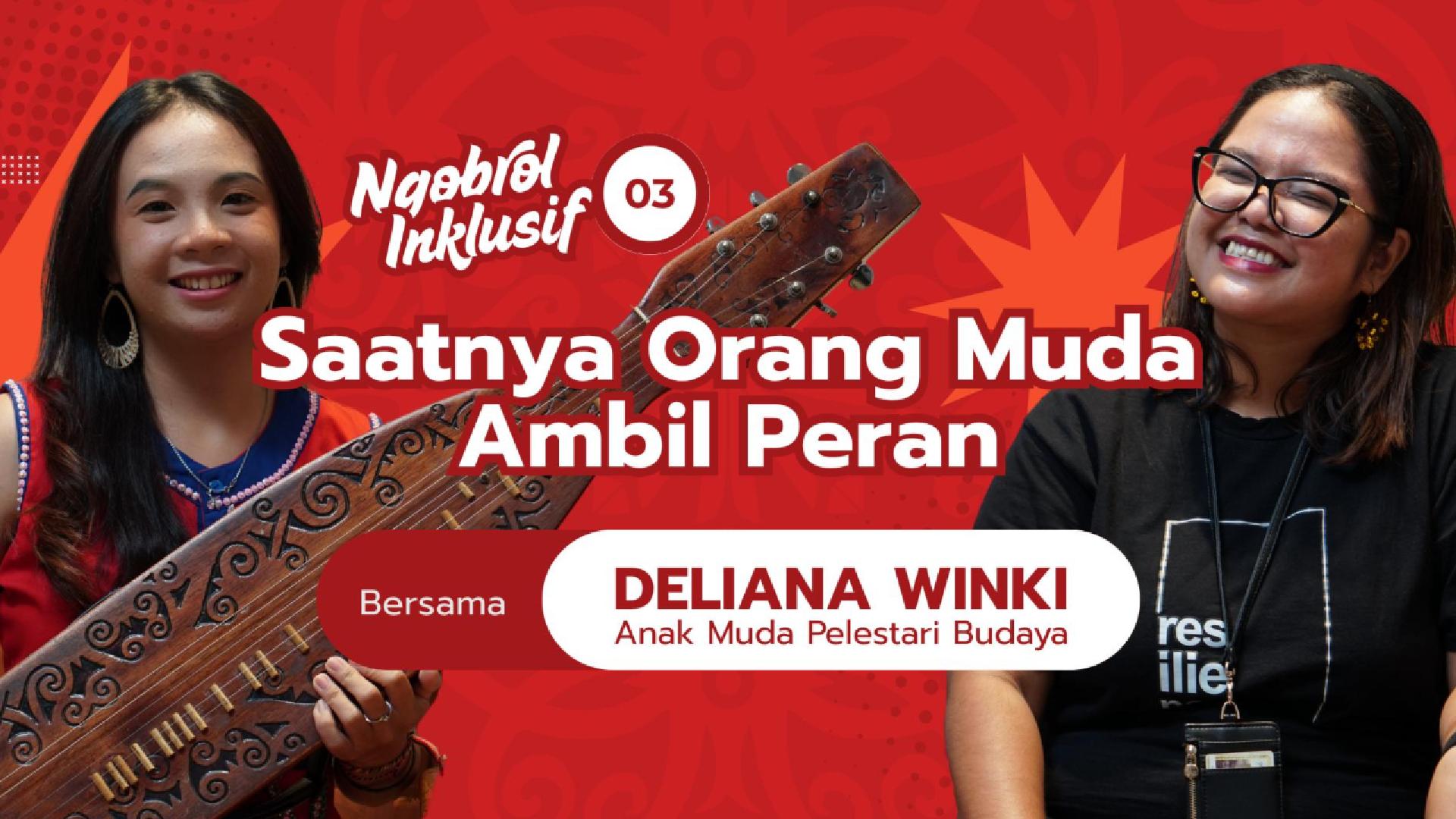

Latest

Video

PUBLICATIONS

PARTNERS

The following are government institutions, both foreign

and domestic, as well as non-governmental organizations

that are our collaboration partners.